Las Vegas NWR

Las Vegas NWR

Las Vegas, New Mexico 87701

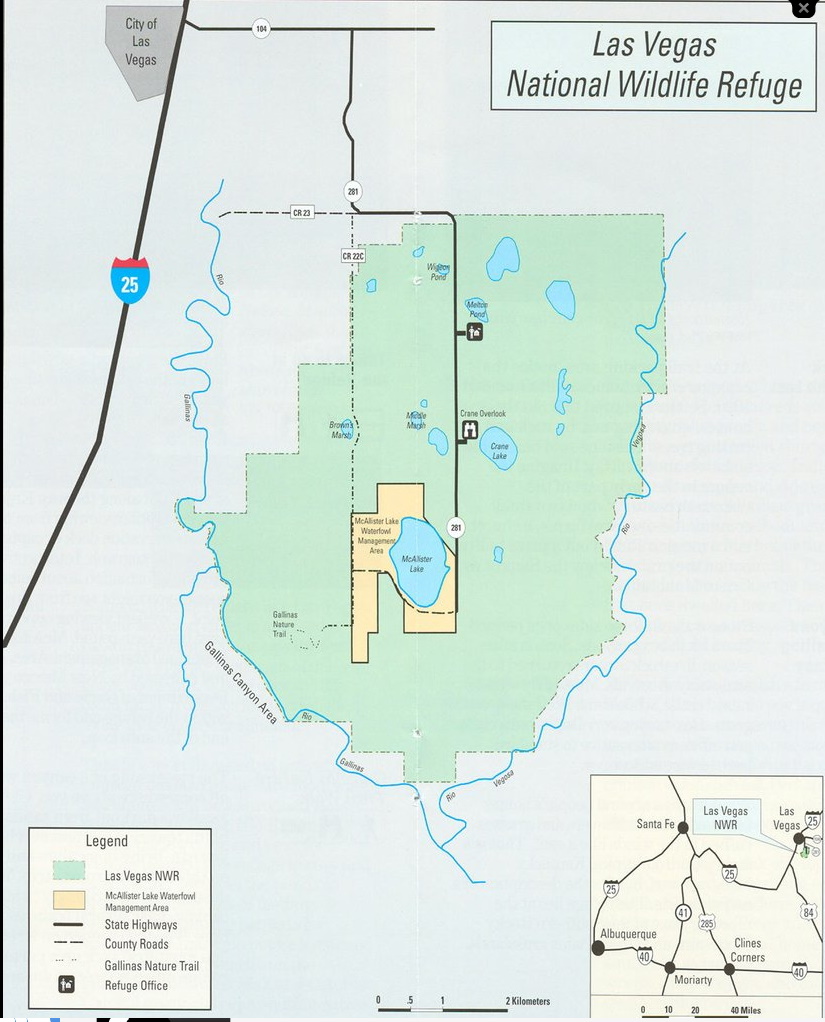

Las Vegas National Wildlife Refuge Official WebsiteLas Vegas National Wildlife Refuge map

Tips for Birding

When submitting eBird observations at Las Vegas National Wildlife Refuge, it is most helpful to start a new checklist for each hotspot within the refuge.

There are four hotspots that are open to the public. Use the general hotspot when you have a checklist that includes multiple locations, the Auto Tour Loop, or if no other hotspot or personal location is appropriate for your sightings.

In addition to the overall Refuge hotspot, there are 2 specific hotspots on the Refuge, plus 1 at the inset wildlife management area. Please do not record for these specific hotspots what you observe in other areas of the Refuge, even though one of them may pop up on your phone as the nearest hotspot; instead record observations outside these well-defined areas as occurring at the general Las Vegas NWR hotspot.

There are areas of the National Wildlife Refuge that are currently closed to public access.

- Bentley Lake, which is the area on the refuge most likely to have water, is not a hotspot and is not publicly accessible.

- Immediately downstream lies Goose Island Lake, now an ephemeral playa, also publicly inaccessible.

- Further south is Crane Lake; this too is now ephemeral and access is currently closed as the viewing overlook is renovated.

Birds of Interest

Clark's Grebe, Broad-tailed Hummingbird, Long-billed Curlew, Lesser Yellowlegs, Northern Harrier, Ferruginous Hawk, Pinyon Jay, Grasshopper Sparrow, and Chestnut-collared Longspur.

About this Location

The general hotspot for Las Vegas National Wildlife Refuge is the number one hotspot in the county, and one of the top ten in the state, with nearly 300 species reported. However, visitors today may want to have more modest expectations than might be set by historical lists of 30 and 40 species, with counts into the thousands of particular waterfowl species.

Reasons to have lower expectations relate to reduced water and feed on the refuge. Though the Refuge can initially appear to be flat prairie, the terrain hides many depressions and swales. Some of these have been connected by irrigation ditches and piping, such that otherwise ephemerally filled playas are now named lakes. Water diverted from the Gallinas River in spring makes its way through farmlands into Bentley Lake in the north of the Refuge, from where it was once distributed around the Refuge and eventually into McAllister Lake WMA. These bodies of water not only provided habitat for large numbers of winter waterfowl migrants but also sourced water for on-Refuge farming of waterfowl feed crops. However, the combination of long-term drought, reduced allocation of irrigation water, and infrastructure deterioration downstream of Bentley Lake have caused the Refuge and Wildlife Management Area lakes to revert to their ephemeral state, as well as farming operations to cease. The US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) does intend to repair the broken infrastructure and eventually resume farming.

The Las Vegas National Wildlife Refuge offers a wide variety of habitats, though roadside viewing from the 8-mile tour loop (NM-281 and CR-22C, not USFWS-maintained roads) is primarily of ephemeral marsh and short-grass prairie; pond/lake and juniper-pine habitats are most observable in the location-specific hotspots. The US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) asks that you visit the latter only between sunrise and sunset. Though the state and county roads should be open 24 hours a day, the dirt portion of CR-22C around the southern end of McAllister Lake may be impassible after heavy rains. If the weather has been dry, consider pulling off NM-281 at the stone-pillared Refuge entrance sign to scan vegetation lining the irrigation ditch immediately south of there. A little way further south, west of the state road, lies the very ephemeral Wigeon Pond; the shoulder between the road and the fence here is wide enough to accommodate your vehicle, but you are likely to get stuck in soft soil. Continuing south on NM-281, Middle Marsh is located opposite Crane Lake, where parking can more easily be found. Similar to the situation at Wigeon Pond, there is no trouble-free place very near Brown’s Marsh to pull off the county road. Birders keen to view Brown’s Marsh (again, from outside the fence ) may find enough shoulder at the entry point to one of the hunter parking lots (typically closed by a locked gate) on the east side of CR-22C, and walk.

Aside from location-specific hotspots, the Refuge is fenced beyond the road shoulder. Public entry to most of the property, including ponds and marshes just mentioned, is not allowed. Be aware that limited hunting, particularly of geese and elk, is permitted on the refuge, most often from access points off CR-22C.

About Las Vegas National Wildlife Refuge

See all hotspots at Las Vegas National Wildlife Refuge

Spanish for "the meadows," Las Vegas National Wildlife Refuge’s history dates as far back as 8,000 BC when old-world Indians inhabited the high plains area.

Pueblo Indians also spent time living in this region, until the 1100s when drought and Apaches forced them out. In the mid-1500s, Spanish conquistadors and missionaries explored and settled the region, and the influence of Spanish culture is still felt today. Westward expansion continued in the late 1800s, and by the turn of the century, the Santa Fe Trail and the railroad made Las Vegas, New Mexico, the place to be.

In 1965, the Las Vegas National Wildlife Refuge was established by the authority of the Migratory Bird Conservation Action for the benefit of migratory birds. The 8,672-acre refuge represents one of the few sizeable wetland areas remaining in New Mexico. It is open to the public for wildlife-dependent recreation, including wildlife watching, hiking, hunting, educational and interpretive programs, and special events.

Here, the gently rolling prairies of the east abruptly meet the rugged terrain of the mountains, gravel-capped mesas and buttes, and deep, narrow river canyons. The high plains refuge is surrounded on three sides by steep, timbered canyons but within the habitat, there is short and tall-grass prairie, timbered sandstone canyons, piñon-juniper woodlands, wetlands, ponds, lakes, and riparian areas.

Above the timbered canyons, the refuge encircles more than 40 small ponds that provide tubers, seeds, and browse for waterfowl. In addition to the ponds, a number of springs discharge to the surface and support a variety of species, including several native fish like the Rio Grande chub, longnose dace, white sucker, and fathead minnow. These ponds are critical to birds migrating along the Central Flyway as they depend on the refuge as a place to rest and refuel during their long journey.

Nesting on the refuge are nearly one-third of the documented bird species found on the refuge, including long-billed curlews, avocet, Canada geese, mallards, northern pintails, blue-winged and cinnamon teal, gadwall, and ruddy ducks.

The sandhill cranes arrive in the fall as they migrate to their winter home. Bald eagles, northern harriers, and American kestrels are frequently sighted soaring above the refuge scanning the grasslands for prey or attracted to the hundreds of ducks and geese on the refuge’s open waters. Migrating shorebirds like long-billed dowitchers and sandpipers, probe the mudflats in early fall and spring. In the woodlands, wild turkeys wander in search of a meal, and on the prairies. Rocky Mountain elk blend into the grasses, home to badgers and ground squirrels.

Notable Trails

Meadowlark Trail - 0.6 miles

The Meadowlark Trail begins a few steps inside the refuge headquarters and visitor center entrance gate. Visitors are welcome to walk the trail at any time during daylight hours. If the vehicular gate is closed, you may still enter the area via the concrete sidewalk to the right of the gate; the entryway is ADA-compliant. The trail winds completely around the headquarters and visitor center area. Going counterclockwise, it heads south from the concrete sidewalk as a crushed-fines-surfaced path for a tenth of a mile, becomes a narrow dirt track north for another tenth of a mile, and then is again a fines-covered path as it travels north and back west, where it meets a concrete viewing area with 2 viewing scopes (one of which is sized for wheelchair users). From there, the trail is concrete-surfaced, circling back to your starting point. As of May 2023, only the concrete portion is ADA accessible; the trail has not been maintained since the visitor center closed in 2019 (pre-CoViD). Interpretive signage has deteriorated to the point where some signs are completely unreadable. Plans exist to rehabilitate the trail.

Gallinas Nature Trail - 1.75 miles

This is a self-guided nature trail that meanders through fields of native grasses and wildflowers, past historic ruins, and descends approximately 250 feet into one of the many box canyons that surround the refuge. As you descend into the canyon, you will find an oasis in this arid zone - a small seep, surrounded by vegetation, which provides habitat for an assortment of small fish, amphibians, crustaceans, and aquatic insects. Continuing on the loop trail, on the western side of the canyon, enjoy being surrounded by the sweet smell of piñon, juniper, and ponderosa. Along this walk, listen for the call of a canyon wren and keep a lookout for wild turkey ahead or American kestrel up above.

Auto Tour Loop - 8 miles

Difficult to drive after rain.

The loop is accessible year-round, although occasionally some parts of County Road 22C become difficult to drive after heavy rain. Informational leaflets, including a map of the refuge and the bird species list, are available during office hours or outside the main entrance, at the kiosk.

The Las Vegas National Wildlife Refuge website has descriptions and maps of hikes at Las Vegas National Wildlife Refuge.

Features

Restrooms on site

Roadside viewing

Entrance fee

Content from Las Vegas National Wildlife Refuge Official Website and John Montgomery

Last updated September 24, 2023

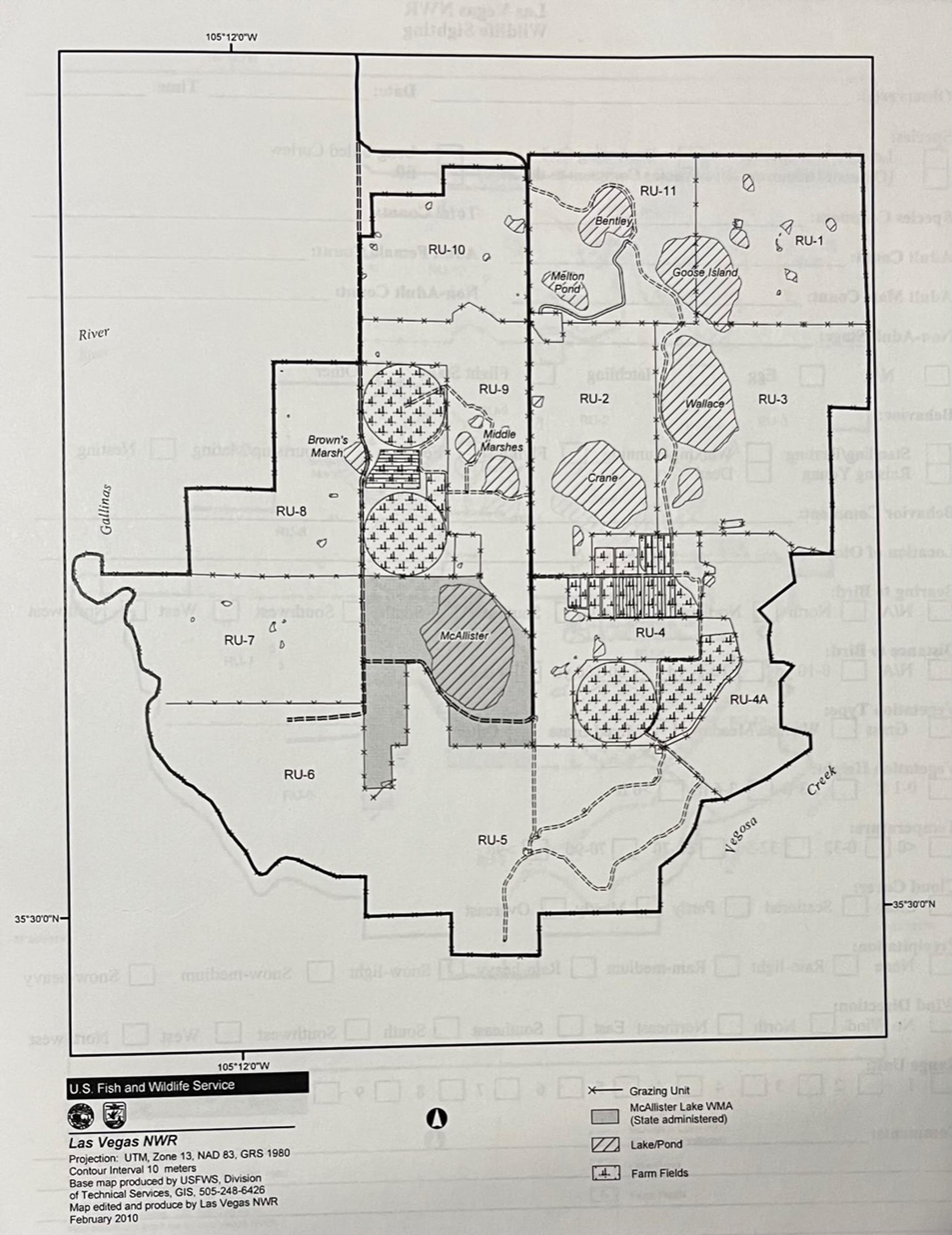

Refuge map, showing range unit numbers

Refuge map, showing range unit numbersJohn Montgomery